Researchers from the University of Pennsylvania have transformed the deadly Aspergillus flavus fungus, historically associated with the curse of the pharaohs, into a promising cancer-fighting agent, paving the way for the discovery of more fungal-derived medicines.

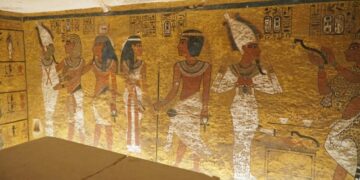

When archaeologists uncovered the tomb of King Tutankhamun in the 1920s, a series of mysterious deaths among the excavation team sparked tales of a pharaoh’s curse. Later, medical experts speculated that dormant fungal spores could have contributed to these fatalities.

In the 1970s, a group of scientists who explored the tomb of Kazimir IV in Poland faced a similar fate, with ten out of twelve succumbing to illness shortly after. Discoveries suggested that the tomb harbored Aspergillus flavus, known for its toxins that can trigger lung infections in those with compromised immune systems.

Now, this same fungus is the basis for an exciting new cancer treatment.

“Fungi have given us penicillin, and these findings indicate that many more natural product-derived drugs are still waiting to be uncovered,” states Sherry Gao, associate professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering and senior author of the study published in Nature Chemical Biology.

The treatment involves a class of peptides known as ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs). Although thousands of RiPPs have been identified in bacteria, very few have been discovered in fungi. To explore further, the researchers examined twelve Aspergillus strains, initially suggested to harbor these compounds, and pinpointed Aspergillus flavus as particularly promising.

After isolating four distinct RiPPs, they discovered these molecules feature a unique structure characterized by interlocking rings. The research team named these previously undescribed compounds aspergimicins, reflecting their fungal origin.

Even in their unmodified form, when tested with human cancer cells, the aspergimicins exhibited significant medical potential, with two of the four variants showing strong efficacy against leukemia cells. One variant, enhanced with a lipid—a fatty molecule found in royal jelly for nurturing bees—performed comparably to FDA-approved leukemia treatments like cytarabine and daunorubicin.

Further investigations suggested that aspergimicins likely interfere with cell division processes.

Importantly, these compounds showed minimal to no impact on breast, liver, or lung cancer cells, indicating that their effects are selectively targeted, which is essential for prospective drug therapies.

The researchers also identified similar gene clusters in other fungi, hinting at the presence of more fungal RiPPs waiting to be discovered.

The next phase involves testing the aspergimicins in animal models, with aspirations of progressing to clinical trials in humans in the future.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions