Eight-four years back, a somber chapter in modern Greek history unfolded with the entry of German forces into Athens, marked by the ominous display of the swastika atop the Acropolis after the Greek flag was taken down. This pivotal moment followed the contentious surrender led by General Georgios Tsolakoglou, a subject we will delve into shortly. It coincided with the collapse of front lines, the flight of King George II and his government to Crete, and the hurried exit of British troops to the Eastern Mediterranean. Let’s review the sequence of events that led to this critical day.

The Fall of Frontlines Following Tsolakoglou’s Surrender

On April 20, 1941, at 6:00 PM in Votonosi, just 10 km from Metsovo, Lieutenant General Tsolakoglou and Brigadier General Sepp Dietrich from the LSSAH signed an armistice protocol with conditions that initially appeared advantageous for Greece. However, the Italian intervention added a layer of complexity. The definitive agreement was reached in Thessaloniki on April 23, 1941, involving Tsolakoglou, General Jodl, and Italian representative Ferrero.

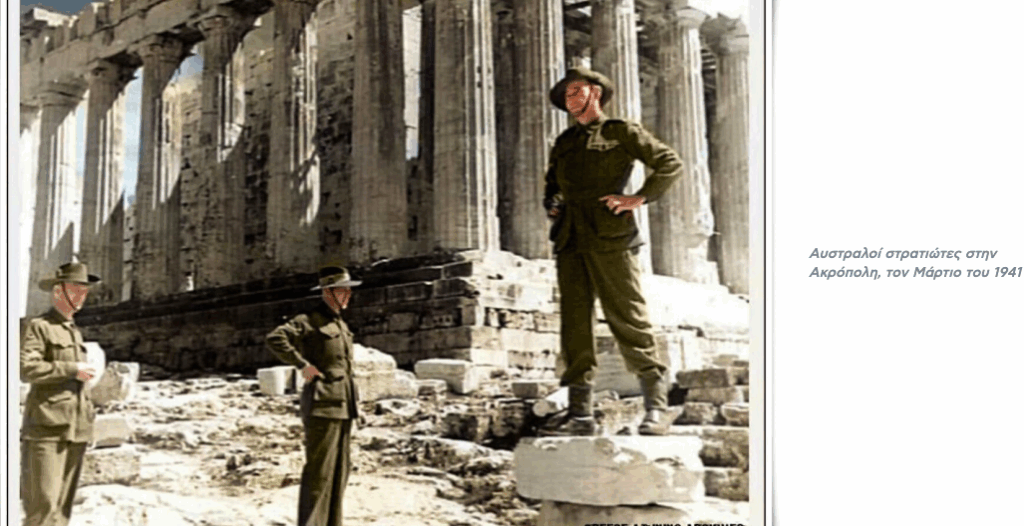

On April 22, the Germans launched an assault on the Thermopylae Pass, which was defended by the 19th Australian Brigade and the 6th New Zealand Brigade. In a tragic turn of events, New Zealand General Freyberg, who commanded forces at the coastal pass, had to retreat to Crete after the Germans captured Thermopylae. As noted in previous articles, Freyberg carries significant blame for the eventual loss of Crete, although he later achieved notable victories in the North African campaign.

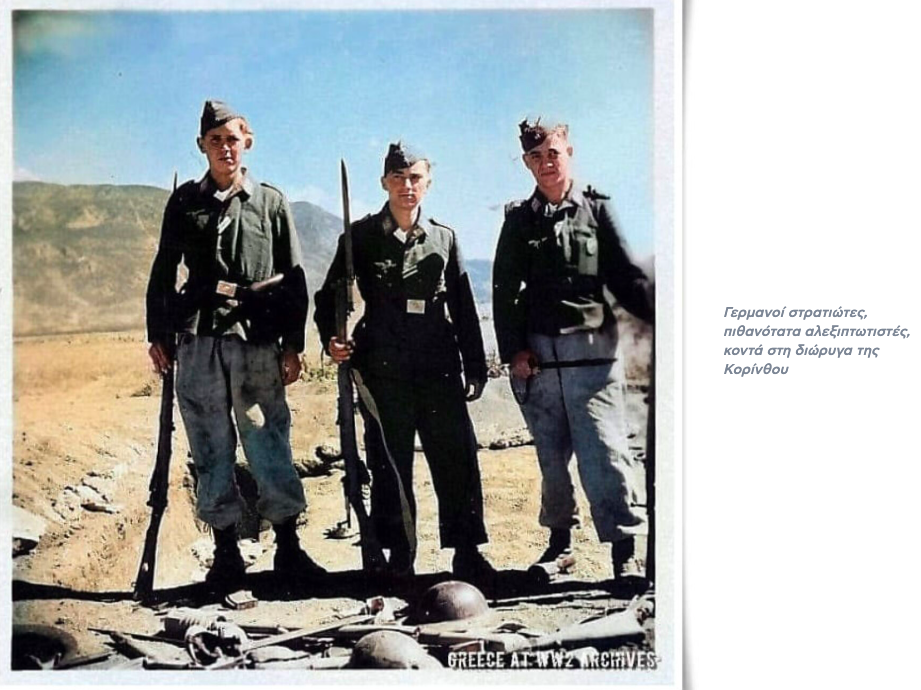

The last stand for British forces was at the Corinth Canal, where the 4th Hussars, Australians, and Maoris defended the area. Anticipating fierce resistance, British Commonwealth forces undermined the bridge with explosives. The Germans, recognizing the challenge, dispatched the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the 2nd Parachute Regiment. After intense combat, during which the bridge was either destroyed in the battle or intentionally by the British to prevent German demolition, British forces retreated to the Peloponnese. With local Greek assistance, they sought evacuation via the ports of Monemvasia and Kalamata to reach the Middle East and North Africa.

The Evacuation of King George II and His Government to Crete

On April 22, 1941, most government officials departed for Crete aboard the destroyer “Queen Olga.” The next day, King George II and the British Ambassador were evacuated via air. For several more days, Deputy Prime Minister Admiral Sakellariou, Minister Maniadakis, General T.G.G. Heywood, and Captain Terl, the British Naval Attaché, remained in Athens, leaving on April 27.

Commander Papagos chose to stay behind, declaring he would “share the fate of his men,” as noted by Dr. I.S. Papafloratos. Despite knowing he was not favored by the Germans, he was not arrested but kept under close observation. Feeling his orders had been disregarded, Papagos submitted his resignation on April 23, 1941, stating, “Because the army under my command surrendered against my orders and without my authorization, I submit a request for retirement.” Previously, on April 21, he had directed the Epirus Army Corps to fight to the last, criticizing Tsolakoglou and demanding his immediate replacement. It’s important to note that Prime Minister Koryzis had tragically taken his own life in Athens on April 18.

On April 23, King George II addressed the Greek populace, concluding with a resilient message: “Do not lose heart, Greeks, even in this difficult hour in our history. I will always be with you. The righteousness of our struggle and God’s support will guide us as we endeavor for ultimate victory amidst our trials. Stay true to the vision of a united, free homeland. Strengthen your resolve. Stand valiantly against adversary aggression and seduction. Be courageous. Brighter days will return. Long live the Nation!”

The Nazis Arrive in Athens (April 27, 1941)

On the morning of Sunday, April 27 (Thomas Sunday), Athens was quiet, with very few people on the streets. Despite the significant religious holiday, only a handful of worshippers attended church services. As the Divine Liturgy aired on the radio, it was abruptly interrupted by an urgent announcement from the city’s military commander, Major General Kavrakos.

“In light of necessity, I command that all movement in the streets of Athens, Piraeus, and the suburbs must cease. All businesses are to close, and residents are to remain indoors, while officers and soldiers stay in their barracks and police at their stations. I prohibit the emergency publication of newspapers. Since the city is unfortified, no resistance will occur. Not a single shot should be fired. Anyone who disobeys will face immediate arrest. Colonel Pezopoulos is appointed as my deputy during my absence.”

Silence enveloped the city. The last British soldiers detonated an ammunition depot in Piraeus. In Athens, only the Nomarch of Attica and Boeotia, Konstantinos Pezopoulos, Mayor Ambrosios Plytas, and the fortress commander were present on behalf of the authorities. They formed a committee that included the Mayor of Piraeus, Michail Manouskos, and Colonel Konstantinos Kanellopoulos, who spoke German. The Archbishop of Athens, Chrysanthos, refused to join.

The committee members ultimately surrendered unfortified Athens to the Nazis after discussions with the German military attaché, Lieutenant Colonel von Hohenberg. They awaited the German commander at the crossroads of Kifisias Avenue and Alexandras Avenue starting at 8:30 AM. Colonel Otto von Seiben arrived at 10:15 AM, accompanied by aides, and approached the committee members. Following a military salute, he awaited the military attaché’s introduction.

Amidst an atmosphere of tension and emotion, those present bowed their heads, bracing for the formal handshake. Colonel von Seiben greeted them and suggested they sit at the nearby café “Parthenon.” Many silent Athenians observed the dramatic unfolding of events.

To mask his nerves, Kavrakos chain-smoked. He then addressed the German officer, with Kanellopoulos translating his words into German: “The local military and political authorities, including General Kavrakos Christos, Senior Military Commander of Attica and Boeotia, Pezopoulos Konstantinos, Nomarch of Attica and Boeotia, Plytas Ambrosios, Mayor of Athens, and Manouskos Michail, Mayor of Piraeus, hereby declare to the commander of the German troops that the cities of Athens are unfortified and will offer no resistance to occupation. All necessary measures have been taken on our part to ensure order until the Germans arrive.”

The German officer reciprocated, delighting in Greek culture and stating, “I assure you that the German army is not here as an enemy but as a friend, bringing peace to Greece. The long-standing friendship between our nations will be reignited soon.” Following the signing of the surrender protocol, Plytas symbolically handed over the city key to the German officer.

Afterward, von Seiben summoned the commanders of smaller units and pointed on a map where they should proceed, scheduling another meeting with Plytas at noon. The last announcement from the Athens Radio Station, written by Dimitrios Svovolopoulos and read by Konstantinos Stauroupoulos, would prove especially haunting in history.

The closing words of the announcement resonate eerily: “Attention! The Athens Radio Station will soon cease functioning under Greek command. It will transition to German control and will disseminate falsehoods! Greeks, do not listen to it! Our struggle continues and will persist until our ultimate victory. Long live the Greek nation!”

Eyewitness Accounts of the German Invasion of Athens

In his book “THE GERMAN INVASION OF GREECE—THE FORGOTTEN ‘NO'” (HISTORICAL QUEST Publishing), Nikos Giannopoulos shares that following the abandonment of the Thermopylae defensive line by British forces, the Germans advanced toward Attica, led by a reconnaissance battalion with motorcyclists and vehicles from the 2nd Armored Division that had traveled from Magnesia to Northern Euboea and then to Chalkida before reaching Central Greece and arriving outside of Athens.

Just after midnight on April 26-27, 1941, the last British forces exited Athens. Witness Andreas Stamatopoulos, who was in Athens with his family, recalled their stay at the “City Palace” hotel on Stadiou Street. According to Giannopoulos’s account of Stamatopoulos’s observations, total silence enveloped the city until 2:30 AM, following the departure of all British vehicles. Sporadic military vehicle movements were noted between 2:30 AM and 4:00 AM. People were restless, peeking through closed shutters in anxiety. Around 8 AM, Stamatopoulos heard the distinct sound of a motorcycle outside their hotel: “A gray military motorcycle with a red flag displaying the swastika sped from Omonia Square toward Syntagma. Suddenly, we felt a lump in our throats; we were now under occupation…”

Indeed, at 8:00 AM on Sunday, April 27, 1941, the 2nd Armored Division’s motorcycles and armored vehicles, under the command of Lieutenant Fritz Dirfling, surged into Athens from the northern suburbs. Witness Nikos Tsertsos was among the first to see vehicles at America Square: “They were riding BMW motorcycles outfitted with sidecars and machine guns. Following them were lightly armored vehicles, proudly displaying the German flag on their hoods for identification.” “It was a cloudy, foreboding day,” recalled Ioannis Antonakeas.

Thirteen-year-old Iakovos Vagiakis observed a German mechanized column from behind his window slats. As they reached Kaningos Square, characterized by circular traffic flow at the time, they stopped, and the soldiers rushed to the orange trees in the square, plucking and devouring the fruit, perhaps confusing them with sweeter varieties! Helene Frangia, a sector leader of the EON, recounted the order from EON’s main command: to respond to the invasion with silence and retreat into their homes… Athens felt lifeless; not a single window was open, nor a soul on the streets. All shutters were drawn. The sounds of boots, tanks, and motorcycles invaded our homes through the windows.”

Vasilis Kouroupos, living in Psiri at the time, recounted, “We could hear the Germans descending Ermou Street. We cried from within, with windows and doors shut.” The late Leonidas Kyrkos, in his last interview with Nikos Giannopoulos, vividly remembered the first sounds of the occupiers: “Locked away in our homes, we could hear the boots of the Germans marching on the street. This marked our first impression of the Occupation.” Young Nikolaos Pavlioglou described what he witnessed on University Street: “The streets were nearly deserted, with very few people present. A handful of individuals clapped, but they were of German descent.”

Nikos Tsertsos reflected on Patision Street: “They arrived from Tatou. There was no gathering, no applause, nothing, unlike the scene in Paris.” Regardless, both were struck by the Germans’ demeanor: “They appeared as rough, weary beings. Unsmiling and silent,” noted N. Pavlioglou. “They looked rugged, marked by dust, exuding warrior essence. They left an indelible impression that evoked fear” (N. Tsertsos). Stathis Tournakis highlighted the striking contrast between German soldiers and disheveled Italian prisoners: “The Germans were soldiers. Until then, we had grown accustomed to seeing poorly dressed Italian captives. The Germans, even as prisoners, emanated a disciplined aura.”

By 9:00 AM, men from another German motorized unit under Captain Jacobi reached the Propylaea of the Acropolis and raised the swastika flag on the Sacred Rock after lowering the Greek flag. It signified a dark moment in Greek history. Helene Frangia remembered: “They ascended the Acropolis, removed our flag, and hoisted the swastika. This etched a deep wound in our hearts.”

In a somber protest against the invasion, Penelope Delta attempted suicide by poison upon the Germans’ entry, passing away on May 2. Her unfulfilled love for Ion Dragoumis, coupled with her struggles with multiple sclerosis, compounded her despair. Her national sentiments played a critical role as well; she had once presciently penned: “In this world, certain things, ideas, principles, and beliefs overshadow even life.” Nevertheless, the indomitable Greek spirit awakened swiftly. As recounted by the late Manolis Glezos, despite the Germans erecting signboards that evening, he and others destroyed them. The next morning, when a German unit arrived at the intersection of Iera Odos and Constantinople, they were at a loss for direction…

Epilogue

Ultimately, Kalamata was the last city in mainland Greece to succumb to German forces after a fierce battle with the British on April 28, 1941. During a speech at the Reichstag on May 4, 1941, Hitler acknowledged, “In history, I must concede that, of all our adversaries thus far, the Greek soldier demonstrated remarkable bravery, surrendering only when all resistance became futile. Henceforth, I have decided not to detain any Greek soldiers, and officers shall retain their personal weapons.”

Sources: Dr. Ioannis S. Papafloratos, “The History of the Greek Army 1833-1949,” SAKKOULAS Publications, 2014; Nikos Giannopoulos, “THE GERMAN INVASION OF GREECE – THE FORGOTTEN ‘NO’,” HISTORICAL QUEST Publications, 2015.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions