Today marks the 81st anniversary of the historic D-Day landing on June 6, 1944, when the Allied forces stormed Normandy.

This pivotal win set the stage for the Allies’ ultimate victory in World War II. In this piece, we will delve deeper into the details of D-Day, the initial phase of the Allied campaign to liberate France and Europe.

When and Who Planned the Allied Landing in Normandy

The Normandy invasion, known as “Operation Overlord,” transpired on June 6, 1944. The term “D-Day” simply represents “Day,” indicating an unspecified future date for a planned military operation.

Since the evacuation of Dunkirk in 1940, which saw the escape of 330,000 surrounded soldiers, the liberation of occupied Europe had been a primary goal for the Allies. However, a series of defeats initially stalled these efforts. Despite Hitler’s cancellation of his planned 1940 invasion of Britain, his forces continued to secure victories in North Africa and Russia.

Things took a turn during the winter of 1942 when German troops at Stalingrad were encircled and ultimately surrendered, marking a significant loss. In North Africa, the British 8th Army achieved a crucial victory at El Alamein, while American forces began to find success in the Pacific after the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941.

In the North Atlantic, the Allies effectively countered German submarines, leading Admiral Dönitz to conclude by late spring 1943 that “the Battle of the Atlantic was lost.”

This development was crucial as it allowed large numbers of American soldiers and vast quantities of war supplies to reach Britain unimpeded.

During the Casablanca Conference in January 1943, President Roosevelt persuaded a hesitant Churchill to begin planning for an intervention in France, leading to the establishment of an Allied staff under Lieutenant General Frederick Morgan with the directive: “Defeat the Germans in Northwest Europe.”

The definitive decision was reached at a Washington conference in spring 1943. In December of that year, General Dwight Eisenhower—dubbed “Ike”—was appointed as Supreme Allied Commander, with General Bernard Montgomery overseeing the 21st Army Group, which encompassed all land forces for the invasion of France. Morgan’s staff became known as the “Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force.”

Headquartered at Norfolk House in London, the command moved to Bushy Park in West London by March 1944, with part of the team based at Southwick House in Portsmouth. Eisenhower’s team numbered around 900 personnel.

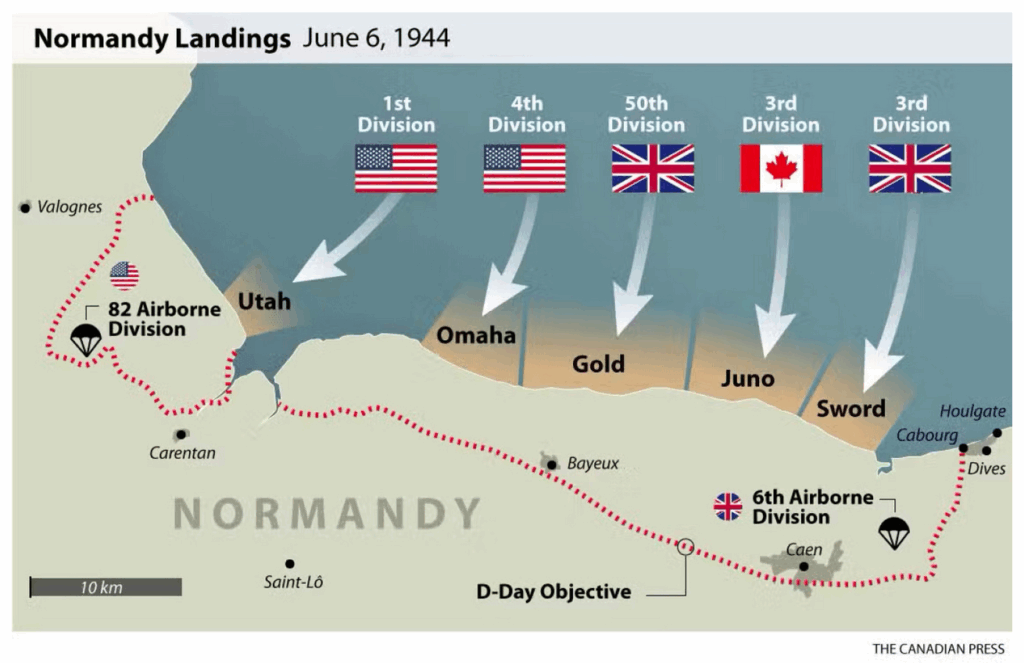

Morgan initially planned for an amphibious landing with three divisions at Normandy, where defenses were considered weaker than at Pas de Calais. Eisenhower and Montgomery expanded this plan to include two additional divisions and a substantial airborne contingent, extending the landing area along the Normandy coast to cover 100 kilometers from Sainte-Mère-Église to Lion-sur-Mer.

The Allied Forces

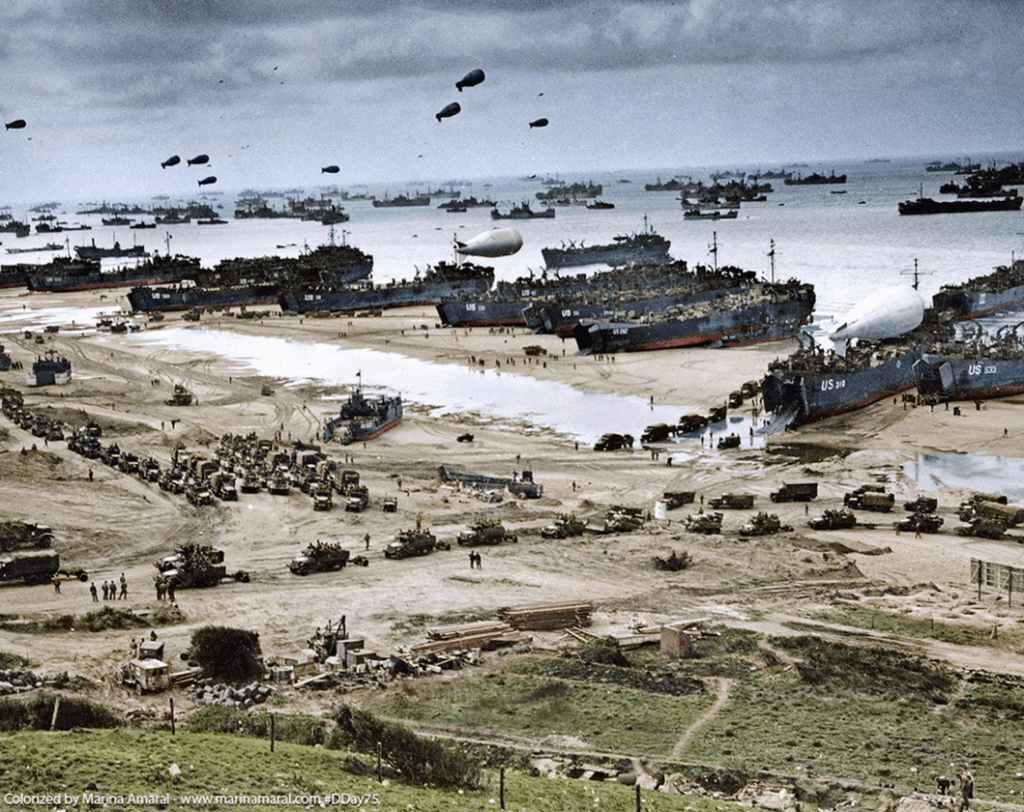

Eisenhower was charged with organizing an unprecedented naval fleet for the operation, initially slated for May but postponed to early June 1944 due to severe weather conditions. The operation commenced on June 6, rather than June 5.

The armada assembled comprised 1,200 warships, 10,000 aircraft, 4,126 landing crafts, 804 transport vessels, and numerous tanks. A total of 156,000 troops were deployed to Normandy: 73,000 Americans and 83,000 British and Canadian forces. Among them, 132,000 crossed the English Channel, while the remainder arrived by air.

The selected landing beaches spanned from the Orne River estuary to the southern tip of the Cotentin Peninsula. American forces were assigned to the western sectors, while British and Canadian troops landed in the east.

The initial assault forces under British General Bernard Montgomery included:

a) The Canadian 1st Army under Lieutenant General H.D.G. Crerar, the British 2nd Army led by Lieutenant General Miles Dempsey, and the British 1st and 6th Airborne Divisions, and

b) The American 1st Army along with the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions under Lieutenant General Omar N. Bradley.

The Operation

On June 6, 1944, Allied troops stormed five beaches in Normandy, codenamed: Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, and Sword.

Except for “Bloody Omaha,” which faced ferocious German resistance, Allied forces made relatively swift landings across the other sectors.

By nightfall, substantial beachheads had been established in all sectors, marking the beginning of the German’s countdown. The fighting continued beyond this point, with the British not capturing Caen until July 9 instead of June 6, and the Americans taking Cherbourg on June 26.

Reasons for the German Defeat

The Germans faced the significant challenge of defending 3,000 miles of coastline along Western Europe and half of the Netherlands to the rugged Italian border. Their 59 divisions in Western Europe were primarily “static,” while 10 operational Panzer divisions remained adaptable.

The Allies launched a decisive and timely assault amidst divisions among German generals regarding the best response to the invasion. Although Hitler had made preparations, the inevitable defeat loomed large…

Epilogue

The Allies’ success in France can be largely attributed to Dwight Eisenhower, whose last name, of German descent, translates to “iron worker.” The substantial impact of aircraft that targeted bridges across the Seine and Loire rivers effectively hampered German supply lines.

Both sides endured substantial losses. The Allies experienced 36,000 casualties and about 200,000 wounded, with 4,000 tanks destroyed. The Germans lost approximately 300,000 troops (with two-thirds captured), and of their 2,000 tanks, merely 120 made it east of the Seine.

The Luftwaffe was unable to influence operations significantly, producing only one-sixth of the aircraft numbers that the Allies possessed in 1943.

We conclude with a story of a remarkable Luftwaffe pilot who later became a successful industrialist. In the early hours of June 6, 1944, while on patrol, he observed the invasion armada: 7,000 ships carrying 160,000 troops, with numerous planes overhead.

“At that moment, I realized the war was lost,” he remarked. Thanks to the cloud cover, he shot down six Allied aircraft before landing due to low fuel.

Simultaneously, once-powerful German submarines managed to sink merely one ship—a Norwegian destroyer. The battle was resolved almost before it truly began as the Allies broke the German encirclement and commenced their rapid advance into the heart of Europe…

Ask Me Anything

Explore Related Questions