On the occasion of the 572nd anniversary of the fall of Constantinople to the Ottomans, we are pleased to share the latest insights into Constantine, drawn from the esteemed work of prominent Byzantinist and Professor Emeritus of Medieval and Byzantine History at the University of Peloponnese, Mr. Alexis G.K. Savvidis. His book, titled “For a New Biographical Dictionary of Byzantium: An Introductory Contribution,” Volume A, Papazisis Editions, second edition, 2024, serves as our reference.

Who was Constantine XI Palaiologos?

Constantine XI Palaiologos was the last ruler of the Palaiologos dynasty (the tenth in the line) and the final champion of the medieval Greek heritage. Born in Constantinople (Byzantium) on March 12, 1405 (or possibly February 9, 1404), he was the fourth of six sons of Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos and Elena Dragaš, of Serbian descent, from the distinguished Dragas family.

As a result, he is frequently referred to as Constantine Palaiologos-Dragaš. Manuel II ruled from 1391 to 1425 before being succeeded by his eldest son, Constantine’s brother, John VIII Palaiologos, who governed from 1425 to 1448. Constantine served as co-emperor with John from 1423 to 1424 and again from 1437 to 1441.

572 years since the fall of the city – His life, reign, and tragic end

After a short period in Tauris, Constantine moved to the Peloponnese, where he, alongside his younger brothers Theodore and Thomas, administered the Despotate of the Morea, reclaiming territories previously under Frankokratia. Their joint rule in the Peloponnese led to rising tensions.

Ultimately, Theodore and Thomas assumed control of the Despotate, while Constantine traveled to Constantinople to assist John VIII. After 1441, he returned to the Peloponnese, but his relationship with the Turks forced him back to Constantinople (1442–1443) to support John VIII. From 1443 to 1448, he focused on reorganizing the Despotate’s administration and military in light of the Turkish threat.

Constantine XI Palaiologos, Emperor of Byzantium

Following John VIII’s death in October 1448 without an heir, Theodore and Thomas initially opposed Constantine’s ascension to the throne. Their mother played a crucial role in his favor, and on January 6, 1449, Constantine was crowned “Emperor of the Romans” at Hagios Demetrios in the Morea. He then journeyed to Constantinople, arriving in March 1449. Notably, no other coronation occurred in Hagia Sophia after this event. Theodore and Thomas continued as co-emperors in Mistra until 1460/61.

The Turks on the verge of Constantinople

When Constantine took the throne, the Ottoman Sultan was Murad V. Upon his death in February 1451, he was succeeded by his son Mehmed II (Mehmed the Conqueror), based in Edirne. Initially, Constantine XI maintained a cordial relationship with both Murad and Mehmed. However, his backing of Orhan, a rival for the sultanate, strained relations. It quickly became apparent to Constantine that the Turks were planning to attack and seize Constantinople.

1452-1453: The siege and fall of Constantinople

From April to August 1452, Mehmed II constructed the formidable fortress of Rumeli Hisar on the European bank of the Bosporus, opposite the earlier-built Anadolu Hisar by Bayezid I, known as the “Lightning.” According to Chalcondyles, from Rumeli Hisar, Mehmed could completely control the maritime access to the Byzantine capital from both the Black Sea and the Sea of Marmara.

The Ottoman siege tightened following victories by Mehmed’s pro-war allies, led by Grand Vizier Halil Pasha Jandarli, who had initially been bribed by the Byzantines to persuade Mehmed against attacking Constantinople.

Today’s Rumeli Hisar

Constantine’s desperate measures to bolster the city’s defenses

Confronted with impending danger, Constantine XI sought to establish a modest defense. However, the empire had already diminished to Constantinople, a few Aegean islands, and the Despotate of the Morea. He looked for help from his brothers in Mistra, but they faced attacks from the aging Turahan Bey and his sons Omer and Ahmed Bey.

Constantine’s efforts to secure aid from Pope Nicholas V (1447–1455) and the West proved futile. The dire economic conditions of the Byzantine Empire, heavily indebted to Venice and suffering from inflation and a debased currency (the poorly minted “stavrat” coins), compounded his challenges.

Moreover, as a moderate supporter of ecclesiastical union, Constantine aimed to acknowledge the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438–1439). On December 12, 1452, he even led a joint Orthodox and Western liturgy in Hagia Sophia, sparking outrage among many citizens who preferred the sentiments of the “Great Duke” Loukas Notaras, who believed it better to see a sultan’s fez in Byzantium than a Latin mitre.

The unequal struggle of Constantinople’s defenders against the Turks

The Peloponnesian cardinal Isidore, previously Metropolitan of Russia, combined forces with 2,000 foreigners (including 700 Genoese) led by the fearless John Longo Justinian, bringing the defending forces to between 5,000 and 8,000 Byzantines. They faced off against tens of thousands of Turks (estimates range from 100,000 to 400,000, depending on sources).

Constantine fought valiantly alongside his officers and soldiers, refusing to surrender. After a 54-day siege (April 2–May 29, 1453), the city succumbed to the Ottomans. Constantine was killed, likely near the Gate of Saint Romanus, with his friend and historian George Sphrantzes absent at the time to provide an accurate account of his death.

572 years since the fall of the city – His life, reign, and tragic end

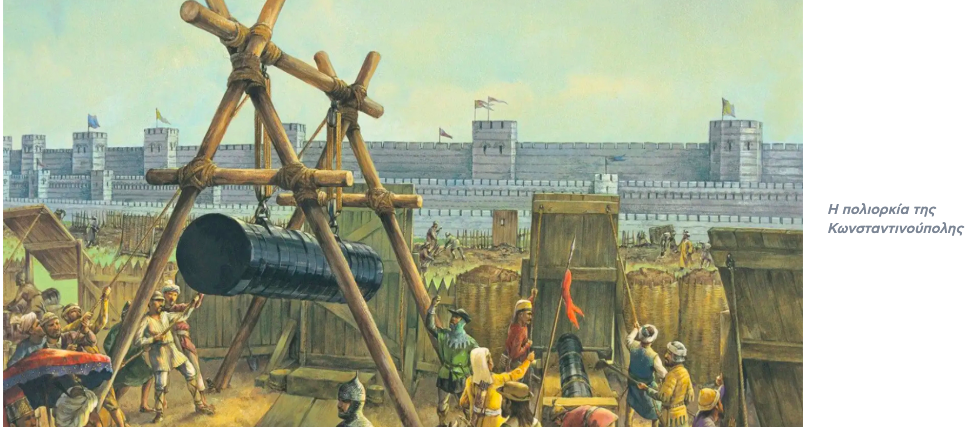

The siege of Constantinople

The immense cannon of Urban outside the city walls

Assessment of Constantine XI Palaiologos

Alexis G.K. Savvidis notes that “the last Palaiologos is among the noblest ruling figures of medieval Hellenism,” although some contemporary historians question his political, military, and diplomatic abilities. Even the admirer of Mehmed II and chronicler of the fall, Michael Critobulus, influenced by Thucydides, likened Constantine XI’s leadership to that of Pericles, albeit without citing primary sources.

The fall of Constantinople deeply unsettled the Byzantines, described as “the common Greek homeland, the seat of learning, the teacher of all sciences, the metropolis of cities,” in the “Monody on the Unfortunate Constantinople,” penned by humanist scholar Andronikos Callistus during that era.

Why is Constantine XI considered the last Byzantine emperor?

Constantine XI Palaiologos fervently supported the revival of Hellenism’s national consciousness, which began to emerge after 1204—the first Latin conquest of Constantinople. He was traditionally referred to as Constantine XI (the eleventh), but recent research suggests he should be numbered as Constantine XII (the twelfth).

The eleventh is now recognized as Constantine XI (Komnenos-Laskaris), a co-founder of the Empire of Nicaea with his brother Theodore I Laskaris (1204–1205). This insightful perspective was proposed by the notable Cretan Byzantinist and scholar Konstantinos Amantos (1874–1960) around 1956 and has gained traction in both Greek and global scholarship in recent years.

The “Marmaromenos Vasilias” (The Marble King)

A recent legend

Constantine Palaiologos as the “Marble King” has transitioned into myth

One of the most common motifs in liberation legends is that of the “Marble King,” found across Greek regions. According to one version, an angel appeared during the final battle on May 29, 1453, to save Emperor Constantine, who was encircled by Turks. The angel took him to an underground cave near the Golden Gate, where he purportedly remains “marbleized” (or asleep) until God sends another angel to awaken him. Upon his awakening, he would return to reclaim the city with his forces, pursuing the Turks to the Red Apple hill for a decisive victory. There is also a well-known legend regarding the last Divine Liturgy in Hagia Sophia, where the priest vanished into the church walls during the service, with the liturgy to resume upon the city’s liberation.

Source: Alexis G.K. Savvidis, “For a New Biographical Dictionary of Byzantium: An Introductory Contribution”, Volume A, second edition, Papazisis Editions, 2024.

We express our sincere gratitude to the esteemed Byzantinist, Mr. Alexis G.K. Savvidis, for his invaluable contributions.

Ask me anything

Explore related questions